Sri Aurobindo (born Aurobindo Ghose; 15 August 1872 5 December 1950) was an Indian philosopher, yoga guru, maharishi, poet, and Indian nationalist. He was also a journalist, editing newspapers such as the Bande Mataram. He joined the Indian movement for independence from British colonial rule, until 1910 was one of its influential leaders and then became a spiritual reformer, introducing his visions on human progress and spiritual evolution.

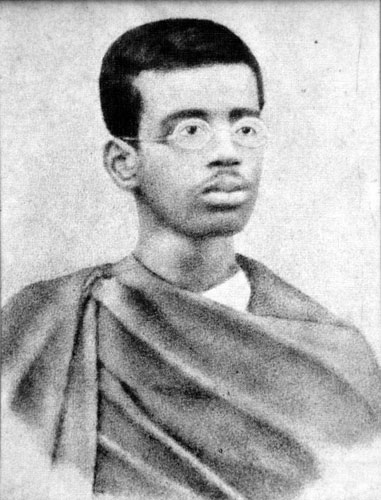

Aurobindo Ghose (15 August 1872 - 5 December 1950) was born to an affluent and anglicised Bengali family in Calcutta (present day Kolkata). His family was originally associated with the Hooghly village of Konnanagar. His father, Krishna Dhun Ghose, was the then assistant surgeon of Rangpur in Bengal and later civil surgeon of Khulna, and a former member of the Brahmo Samaj, a spiritual reformist order which had emerged in nineteenth century Bengal. His mother Swarnalata Devi's father, Shri Rajnarayan Bose was a leading figure in the Samaj. She had been sent to the more salubrious surroundings of Calcutta for Aurobindo's birth. When the time came to name the child, her husband, in a suddeninspiration,chose ‘Aurobindo, a Sanskrit word for lotus. At some point his father, Krishna Dhun Ghose, added an English-style middle name in honour of his friend Annette Akroyd. The child was thus named Aurobindo Acroyd Ghose.

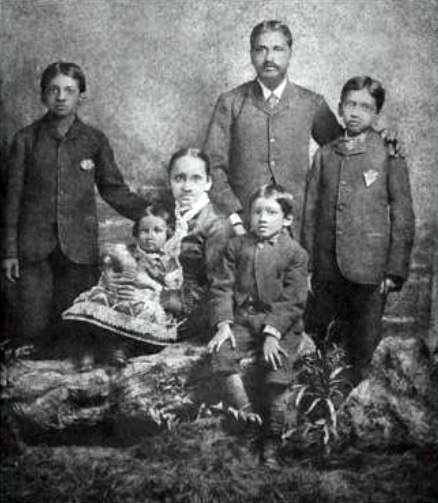

Aurobindo Ghose (seated centre next to his mother) and his family in England, 1879

Aurobindo had two elder siblings, Benoybhusan and Manmohan, a younger sister, Sarojini, and a younger brother, Barindra Kumar (also referred to as Barin)

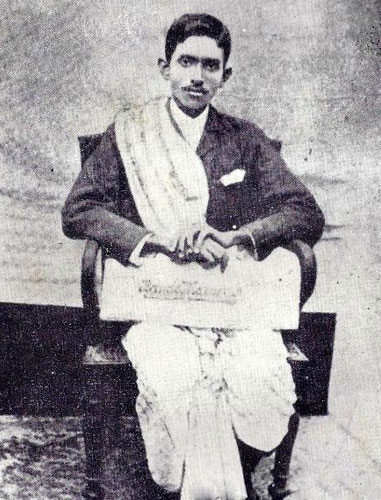

Aurobindo (seated) with elder brothers, Benoybhushan and Madhusudan Ghose

In 1879, the boys father, Dr. Ghose, left them in England for 14 years to become Englishmen. After five years in Manchester, their guardian emigrated to Australia, and they moved to London to attend St Pauls and live with the guardians aged mother. When she fell out with Ghoses brother four years later, the boys were left on their own.

Money had not come from home for a while. Ghose later remembered spending 1888-1889, one of the coldest winters on record, with no wood for a fire and no overcoats. He said his classmates noticed as his clothing grew more and more dirty and unkempt.Relief came in the form of a scholarship to the University of Cambridge. The stipend paid enough to sustain all three brothers, but not to pay for extras.

Besides tailored suits, the scholarship entitled Ghose to wear the open scholargown of the Kings academic elite (Kings College).Thus clad, he entered the ICS (Indian Civil Service) programme and learned for the first time about India. Aurobindo, who is said to have spoken Bengali with an accent, is said to have first studied the language at Cambridge. He also became involved with other Indian students and decided that he would not want to serve the British Raj. Some say that it was in his later years at Baroda that he taught himself Bengali and Sanskrit with greater determination.

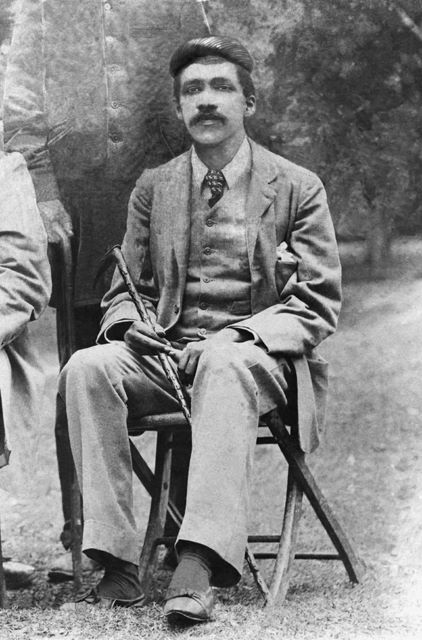

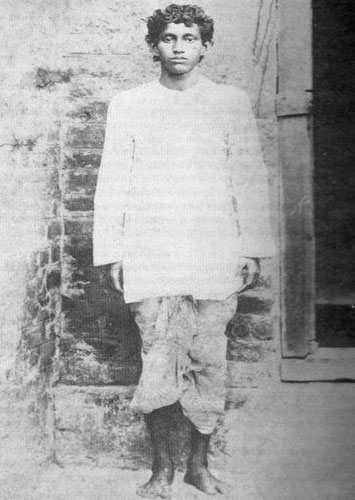

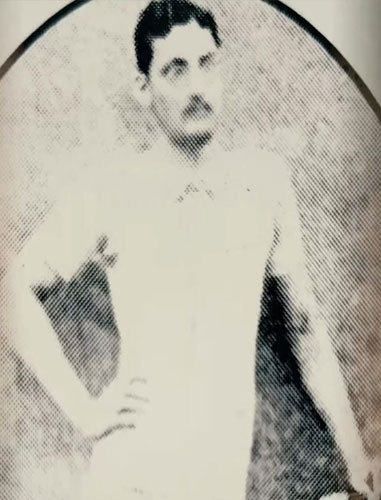

Fig.3. A young Aurobindo Ghose in 1903

In 1893, 21-year-old Ghose stepped off the ship onto Indian soil to learn that his father was dead. He went directly to Baroda, where he worked for Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III (the Maharaja of Baroda State from 1875 to 1939) and taught at Baroda College (now The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda). In his book The Lives of Sri Aurobindo, biographer Peter Heehs wrote that, “He kept his suit, his shoes and socks, his public-school accent—but he did drop his English middle name. From the time of his arrival in Baroda, he became known as Mr. Arvind A. Ghose.” (Heehs, 2008, p.36.)

Aurobindo during his time in Baroda

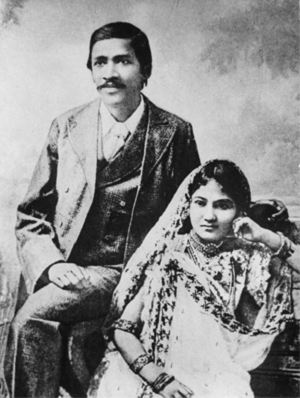

In 1901, aged 28, while visiting Calcutta, he married 14-year-old Mrinalini, the daughter of Bhupal Chandra Bose, a senior official in government service. Aurobindo was 28 at that time. Mrinalini died seventeen years later in December 1918 during the influenza pandemic.

Aurobindo Ghose with wife Mrinalini.

Young and impressionable Aurobindo became increasingly involved in nationalist politics in the Indian National Congress and the nascent revolutionary movement in Bengal with the Anushilan Samiti.The seven political essays published in the Indu Prakash bear testimony to his nascent nationalistic fervour.

A few years after this publication, Aurobindo chalked out a plan of action for the freedom movement of the country and he himself plunged headlong in this movement.

Emblem of Anushilan Samiti

Aurobindo often travelled between Baroda and Bengal, at first in a bid to re-establish links with his parent's families and other Bengali relatives, including his sister Sarojini and brother Barin, and later to establish resistance groups across the Presidency. During this time, Barindra Kumar, the younger brother of Aurobindo, visited Baroda (he had abandoned his studies) and took initiation from his elder brother in the noble mission of serving the motherland.

Aurobindo formally moved to Calcutta in 1906 after the announcement of the Partition of Bengal. In Bengal, with Barin's help, he established contacts and inspired revolutionaries such as Bagha Jatin or Jatin Mukherjee and Surendranath Tagore. He helped establish a series of youth clubs, including the Anushilan Samiti of Calcutta in 1902.

The youth in revolutionary associations like Anushilan Samiti were encouraged to do physical exercises, participate in parades, and undergo martial training. They acquired remarkable skills in wielding sticks (lathi khela). The late Sarala Devi was also involved in this. Much later, she introduced the Veerashtami Vrata (a religious vow) in Bengal.

Around the same time, a meeting took place between Lokmanya Tilak and Aurobindo. Lokmanya had previously suffered imprisonment and became well known in the country. Aurobindo discovered in Lokmanya an extraordinary revolutionary leader. He expressed his contempt for the Reformist Movement of the Congress and explained his own line of action in Maharashtra. This was the beginning of a deep friendship between these two great nationalist leaders.

Barindra Ghose

Aurobindo at a Conference of Nationalist Delegates at Surat in December,1907. Aurobindo, sitting with his hands on the table, flanked on his right by G.S. Khaparde and on his left by Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, speaking

In July 1905, the then Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, partitioned Bengal. This sparked an outburst of public anger against the British, leading to civil unrest and a nationalist campaign by groups of revolutionaries that included Aurobindo and other members of the revolutionary group, Anushilan Samiti.

In the midst of the great turmoil that engulfed the entire nation because of the partition of Bengal, Aurobindo, in that nationwide passion, engaged himself to prepare the ground for an armed revolution. Barindra Kumar Ghose, his younger brother, was particularly enthusiastic in this endeavour. It is on his request that Aurobindo consented to launch Jugantar, a revolutionary daily of that era. Jugantar openly published articles which opposed British rule, supporting martial tactics to overthrow British yoke over Indians. Aurobindo wrote a few articles at the beginning. Barindra Kumar and Upendra Nath Bandyopadhyay were amongst its numerous fire-brand writers. When Jugantar was charged with seditious writings, it was on the advice of Aurobindo that Bhupendra Nath Dutta, brother of Swami Vivekananda, refused to stand up for his own defence in the British court. Sandhya, a newspaper edited by Brahmabandhav Upadhyay, later cooperated with the Jugantar.

Emblem of 'Yugantar' (or 'Jugantar') - Revolutionary Bengali Newspaper The emblem includes the symbols of two faiths, the trident and chakra of Hinduism and the crescent and sword of Islam

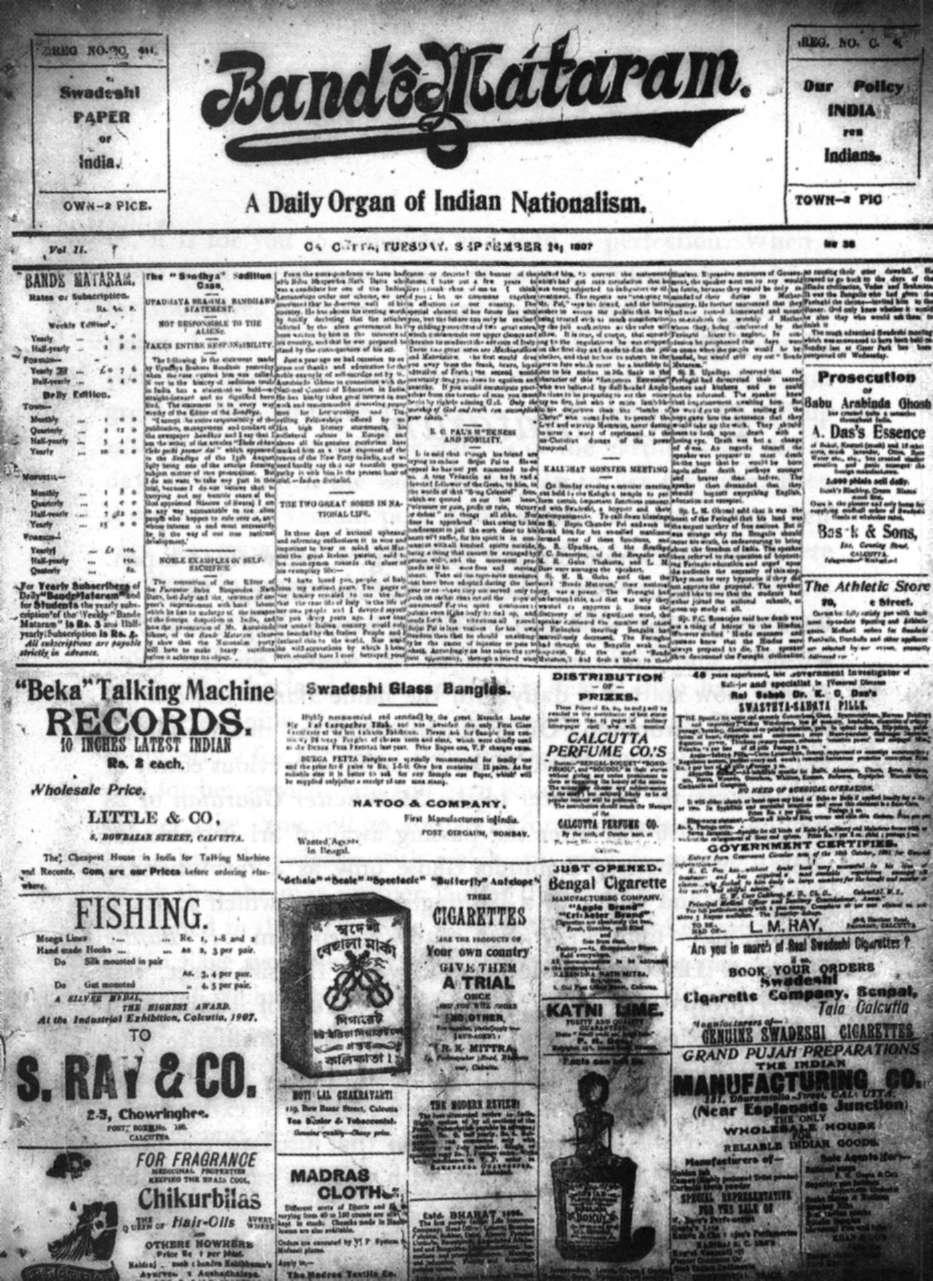

Aurobindo, through his articles in the English daily Bande Mataram, used to propagate the ideals of nationalism, of complete independence, of national education and of national organisation. He used to write also on the course of action needed for the mass movement, for example, swadeshi, passive resistance etc. and criticise the British rule and the British character.

Lajpat Rai wrote (on 4 May 1907, just five days before his deportation) regarding Ghose’ Bande Mataram,

"... I spare no opportunity to recommend your excellent paper to my friends as well as those whom I meet. For me it is generally an intellectual feast and it is my earnest desire that nothing will happen to mar its usefulness. It is doing a splendid service. May it live long is the earnest prayer..."

September 14, 1907,

Bande Mataram. This was an English newspaper edited by Aurobindo. His first preoccupation was to

declare

openly for complete and absolute independence as the aim of political action in India and to insit on

this persistently in the pages of the journal.

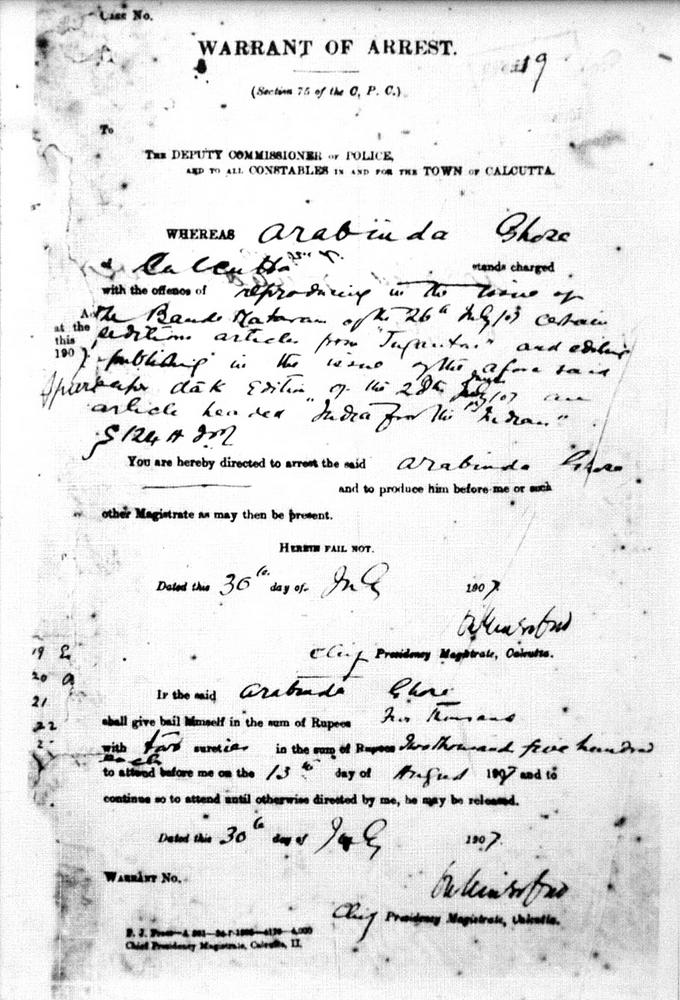

In August, 1907, The British sought to prosecute Aurobindo under section 124A of Indian Penal Code for sedition as the editor of Bande Mataram. The charges were made on the basis of a technical violation of law by 'a reprint of the official translations of certain articles from a vernacular paper, Yugantar, that were related to a Sedition Case and 'an insignificant correspondence which did not even profess to give voice to the policy of the paper'.

Arrest Warrant for Aurobindo Ghose in the Bande Mataram Sedition Case

Aurobindo was arrested on 16th August, 1907 and released on bail the next morning. On September 23, 1907, Magistrate Kingsford ruled that the Prosecution had failed to prove that Aurobindo was the Editor. Thus Aurobindo was acquitted. Kingsford also did not find any evidence to support that "the Bande Mataram habitually publishes seditious matter".

In 1908, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki attempted to kill Magistrate Kingsford, a judge known for handing down particularly severe sentences against nationalists. However, the bomb thrown at his horse carriage missed its target and instead landed in another carriage and killed two British women, the wife and daughter of barrister Pringle Kennedy. This episode is also referred to as the Muzaffarpur Bomb-throwing Incident which turned to be the trigger-point for the Alipore Bomb Case.

Khudiram Bose in Muzaffarpur Jail

Prafulla Chaki after death

News of the bombing reached Calcutta on 1 May 1908, and suspicion was immediately on Aurobindo and Barin. Andrew Fraser, the Governor of Bengal, contemplated the arrest and deportation of the Samiti leadership of the Ghosh brothers, Abhinash Bhattacharya, Hemchandra Das and Satyendranath Bosu. Aurobindo was also arrested on charges of planning and overseeing the attack and imprisoned in solitary confinement in Alipore Jail. The trial of the Alipore Bomb Case lasted for a year, but eventually, he was acquitted on 6th May 1909. His defence counsel was Chittaranjan Das.

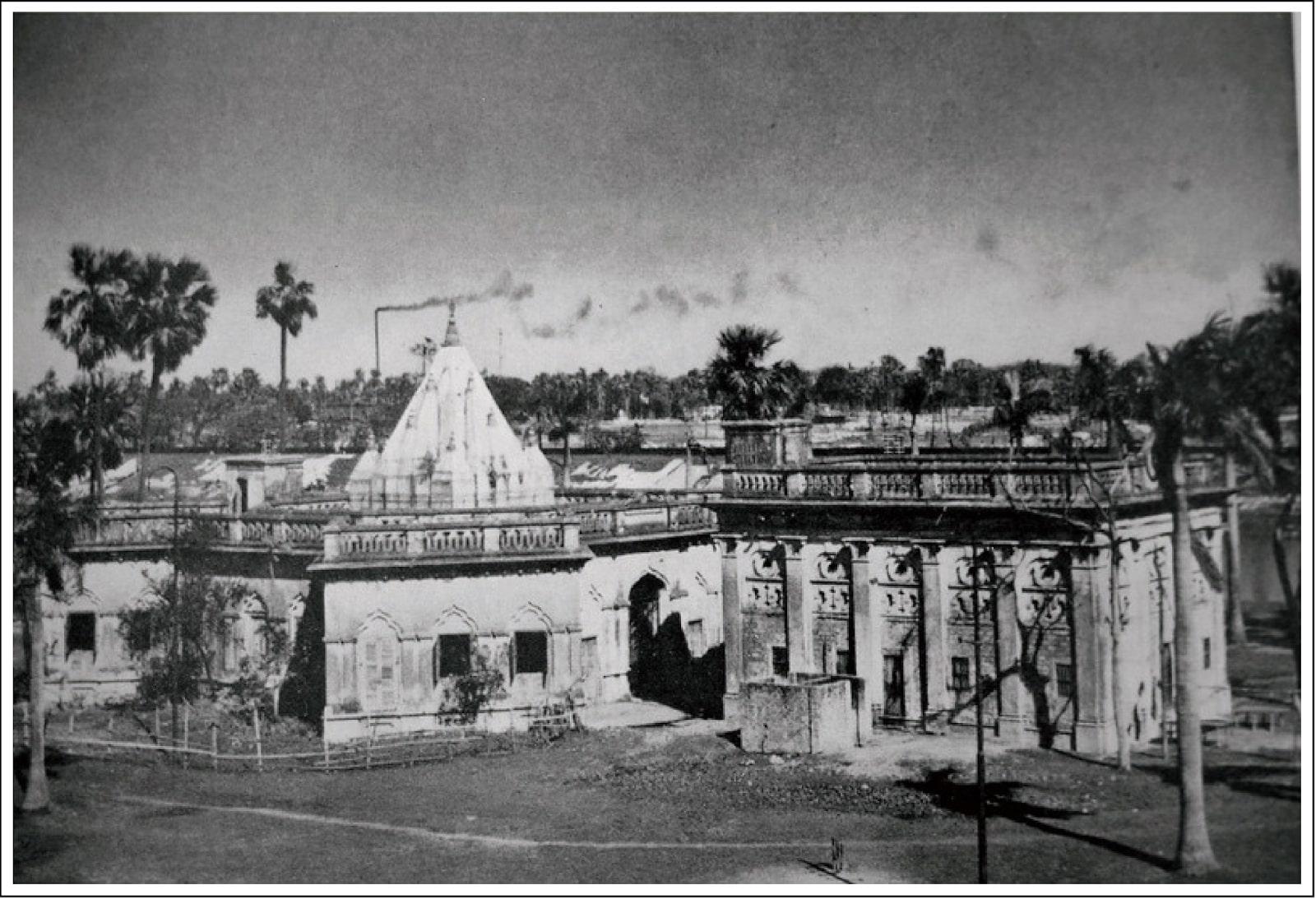

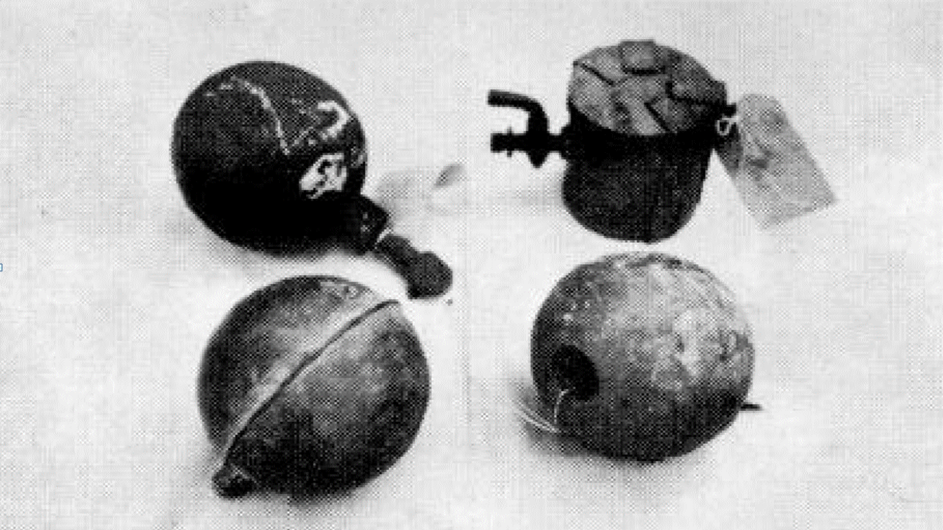

In the aftermath of the Muzaffarpur Bomb throwing incident, the Police raided the property at 32, Muraripukur Road in the wee hours of May 2, 1908. A Bomb-factory was discovered as was a cache of arms, a large quantity of ammunition, bombs, detonators and other tools. They also confiscated revolutionary literature.

Muraripukur garden house, in the Manicktolla suburbs of Calcutta. This served as the headquarters of Barin Ghosh and his associates

Four bombshells found at 134 Harrison Road, one is the brass knob of a bedpost, another the ball cock from a cistern. Image courtesy: Peter Heehs, The Bomb in Bengal: The Rise of Revolutionary Terrorism in India, 1900-1910, New York, Oxford University Press, 1993, p.120.

Fourteen members of the Anushilan Samiti were taken into custody immediately. These include:

The Police also conducted raids at various other places in Calcutta and took several other revolutionaries in custody. The raids continued through the month of May at places across Bengal and more arrests were made:

| Hem Chandra Das | Dindoyal Bose |

| Kanailal Dutt | Narendra Nath Gossain |

| Sushil Sen | Indra Nath Nandy |

| Birendra Sen | Nikhileshwar Nath Moulik |

| Birendra Nath Ghosh | Krishna Jibon Sanyal |

| Hrishikesh Kanjilal | Debabrata Bose |

| Sudhir Kumar Sarkar | Charu Chandra Roy |

| Nirapodo Roy | Bijoy Chandra Bhattacharya |

| Ashok Nandi | Provas Chandra Deb |

| Nagendra Nath Gupta | Balkrishna Hari Kane |

| Dharani Nath Gupta | Bejoy Ratna Sengupta |

| Motilal Bose | Hem Sen |

Some of the undertrials at the Alipore Bomb Case

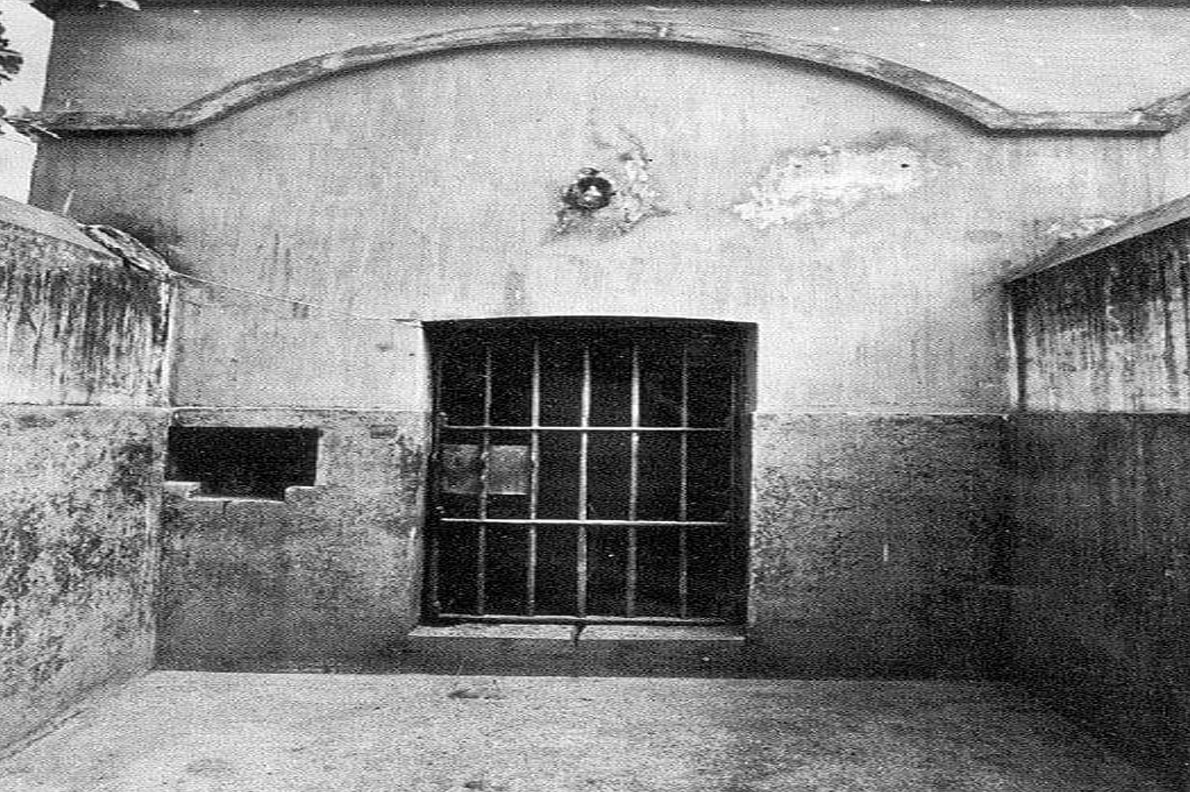

Aurobindo was arrested in connection with the case. Seen as the mastermind behind the bomb-conspiracy and secret activities of the Anushilan Samiti, Aurobindo was kept in solitary confinement at the then Alipore Jail (now known as the Presidency Jail), not too far away from the present Alipore Jail (Independence Museum) premises. During his stay at the jail, Aurobindo wrote in considerable detail with his characteristic wry wit and keen observation of prison life. The works have been compiled as Tales of Prison Life or Karakahini in Bengali.

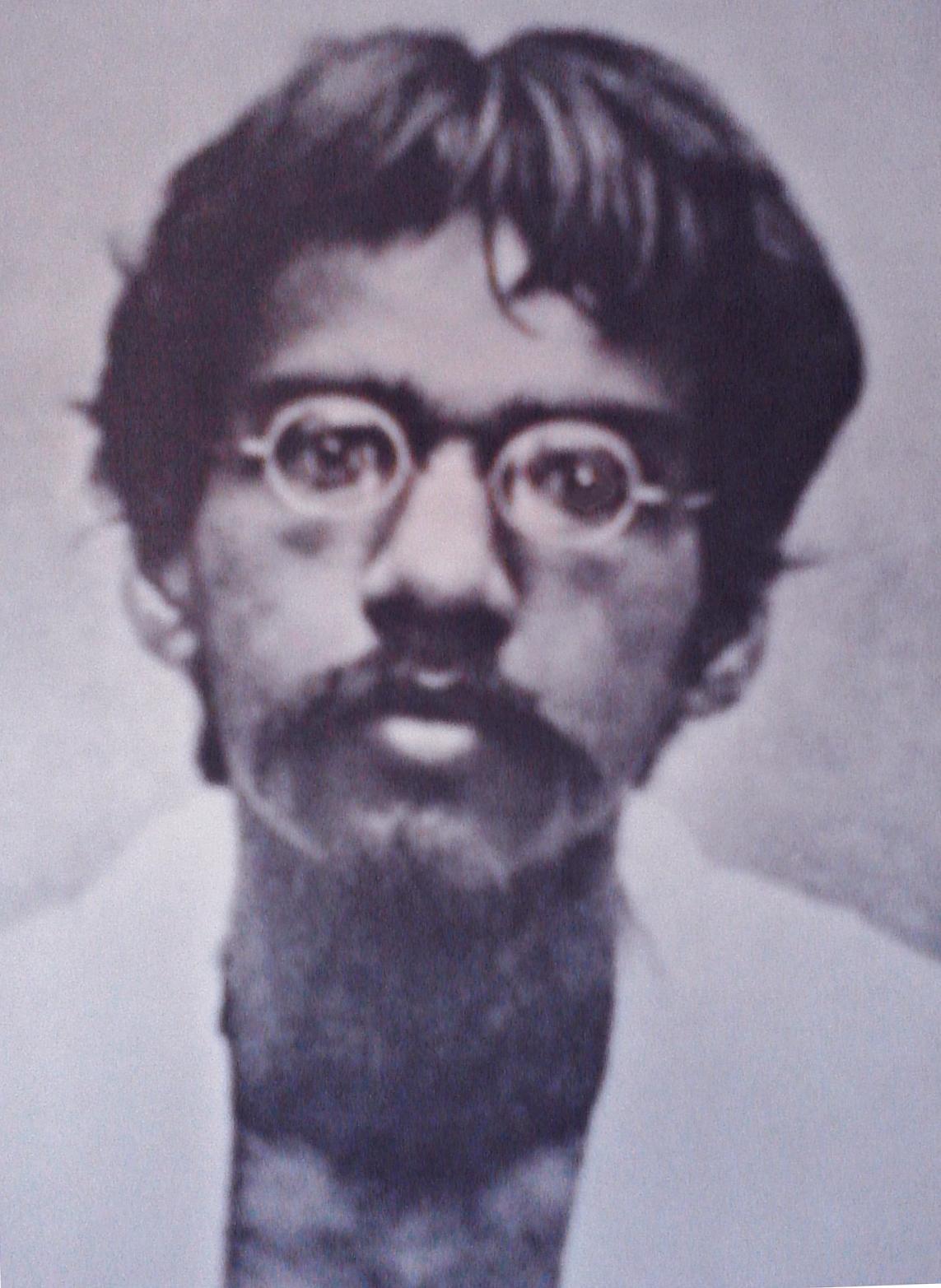

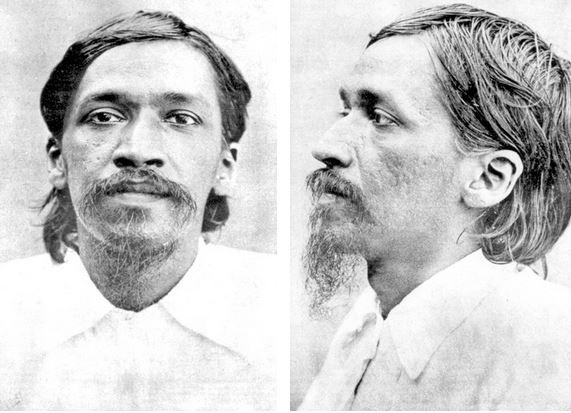

Police photographs of Aurobindo on the day of his arrest in May, 1908

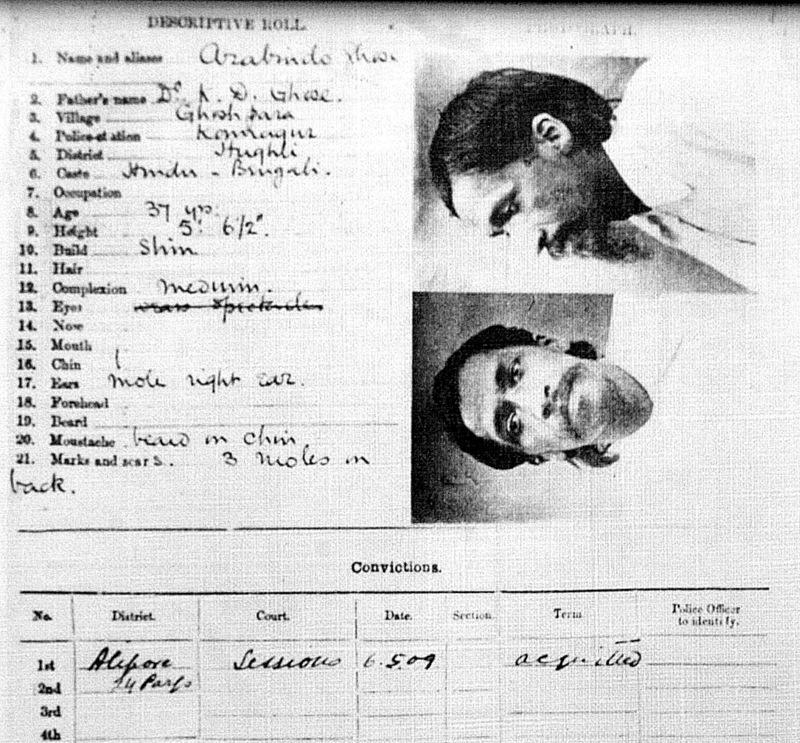

Police descriptive roll on Aurobindo Ghose

Following is an excerpt describing his prison-cell.

My prison-cell was nine feet long and about five or six feet wide. This windowless cage, fronted by a

large

iron barred-door, was assigned to me as my abode. The cell opened into a very small courtyard, paved

with

stones and surrounded by a high brick wall. A wooden door led outside. The door had a small peep-hole at

eye-level, for sentries to keep a periodic watch on the convicts when the door was closed. The door to

the

courtyard of my cell was generally kept open. There were six such contiguous cells known as the 'six

decrees'. The word 'decree' was a reference to the special punishment prescribed either by the Judge or

the

Jail Superintendent in the form of solitary confinement within these tiny, cramped cells.

There were varying degrees of severity even in solitary confinement though. The first degree of severity

consisted of keeping the courtyard doors shut to deprive the prisoner of all human contact. The tenuous

link

with the outside world was then preserved through the eyes of the vigilant sentries and the visits of

fellow-convicts, who came twice a day to deliver meals. It appears that Hemchandra Das was a notch

higher

than me on the scale of the CID's (Criminal Investigation Department) affections, as evidenced by him

being

singled out to undergo this form of punishment.

A still higher degree of severity consisted of having a prisoner's hands bound in handcuffs and feet in

shackles. One might assume that prescription of such a severe form of punishment would require a

suitably

grave offense like physical violence or disrupting the peace in jail. But that assumption would be

incorrect. Even slackness in prison labour or repetition of mistakes in one's assigned work would often

be

adequate cause to invite such harsh punishment.

The legal system disallowed under-trial prisoners to be subjected to solitary confinement or to be held

under such torturous conditions. But such niceties of law were dispensed with when dealing with those

accused in affairs related to the Swadeshi movement or 'Bande Mataram' and hence arrangements were

promptly

made for them as desired by the police.

The solitary cell and basic amenities that were provided to Aurobindo during his time in Jail

Prison Cell where Aurobindo was kept at the Old Alipore (now Presidency) Jail

The Maniktala gardens were under the jurisdiction of the Alipore suburb of Calcutta. On 5 May 1908, Aurobindo and others were produced in front of the chief presidency magistrate's court, where they were allowed access to lawyers for the first time. The case is thus referred to as the Alipore Bomb Case, also referred to as the Muraripukur conspiracy, or the Manicktolla bomb conspiracy. On 18 May, the accused were formally charged in the first hearing of Emperor vs Aurobindo Ghose and others. The charges included "organising to wage war against the government" and charging each individual accused with "waging war against the King". Thirty-eight members of the Anushilan Samiti were presented in Court, and it seemed it was all over for Aurobindo and others when Naren Gossain/ Narendranath Goswami decided to turn approver and Crown’s witness against the other accused.

The prison authorities had shifted Narendra Goswami to the Jail Block where European prisoners were kept, fearing retribution from his revolutionary associates. Kanailal Dutt and Satyen Bose were admitted as patients in the Jail Hospital. Satyen sent a message to Naren expressing his desire to also turn as Crown’s approver.. Naren came to the Jail Hospital along with a convict overseer, Mr.Higgins. Naren, Satyen and Kanai went out to the Verandah to converse in private when Kanai took out his R. I. C. *450 bore revolver and Naren tried to escape in vain. Satyen used a smaller one, a *380 bore, by Osborne, and a scuffle ensued. Naren ran out of the Hospital Gate with Kanai and Satyen in pursuit. Abruptly Naren spun around and fell down dying into the drain. A bullet from Kanai's revolver had punctured his spine. Eventually, nine bullets had been fired in total- five fired by Kanai, and four by Satyen.

Kanai Lal Dutt

Satyendranath Bose

Narendranath Goswami

Both Kanai and Satyen were tried and executed soon after at the Old Alipore (present day Presidency) Jail gallows.

Observing popular support following the executions of Khudiram Bose, Kanailal Dutta and Satyen Bose, the day of the verdict was kept closely guarded. Additional security measures were put in place, with a reserve force of European officers held ready in case of an outbreak of violence and disorder in the streets of Calcutta. Sessions Judge Charles P. Beechcroft delivered his verdict on 6 May 1909, amidst tight security in Calcutta. It is important to remember that Beechcroft and Aurobindo had previously entered the Indian Civil Service Examinations in England in the same year, where Aurobindo had ranked ahead of Beechcroft.

"I now come to the case of Arabinda Ghose, the most important accused in the case. … The point is whether his writings & speeches, which in themselves seem to advocate nothing more than the regeneration of his country, taken with the facts proved against him in this case are sufficient to show that he was a member of the conspiracy. And taking all the evidence together I am of the opinion that it falls short of such proof as would justify me in finding him guilty of such a serious charge."

Photograph of Judge C.P. Beechcroft

In his verdict, Barin Ghosh and Ullaskar Dutt were found guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging (later commuted to life imprisonment). Thirteen others, Upendra Nath Banerjee, Bibhuti Bhusan Sarkar, Hrishikesh Kanjilal, Birendra Sen, Sudhir Sarkar, Indra Nandy, Abinash Bhattacharjee, Sailendra Bose, Hem Chandra Das, Indu Bhusan Roy, Poresh Mullick, Sishir Ghosh, Nirapado Roy were sentenced to transportation for life and forfeiture of all property. Three others, Poresh Mullick, Sishir Ghosh, Nirapado Roy were sentenced to ten years incarceration along with forfeiture of property. A further three Ashok Nandi, Balkrishna Kane, Susil Sen were sentenced to seven years jail terms. Seventeen, including Aurobindo, were found not guilty. One defendant, Kristo Jibon Sanyal, was sentenced to one-year rigorous imprisonment. Two of the 17 acquitted, Dharaninath Gupta and Nagendranath Gupta, were already undergoing a 7-year sentence for conviction in the Harrison Road case, so they were not released. Probash Chunder Dey was re-arrested on a sedition charge under Section 124A, in connection with the publication of the book "Desh Acharjya".The verdict on Aurobindo was passed last. Beechcroft highlighted the lack of concrete evidence linking Aurobindo to the conspiracy in the lack of crown-witness Naren Goswami.

During this period in the Jail, his view of life was radically changed due to spiritual experiences and realisations. Consequently, his aim went far beyond the service and liberation of the country.

Aurobindo said he was "visited" by Vivekananda in the Alipore Jail:

"It is a fact that I was constantly hearing the voice of Vivekananda speaking to me for a fortnight in the jail in my solitary meditation and I felt his presence." (Sri Aurobindo, Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 2006, p.98).

In 1910 Aurobindo withdrew himself from all political activities and went into hiding at Chandannagar in the house of Motilal Roy, while the British colonial government were attempting to prosecute him for sedition on the basis of a signed article titled 'To My Countrymen', published in Karmayogin. As Aurobindo disappeared from view, the warrant was held back and the prosecution postponed. Aurobindo manoeuvred the police into open action and a warrant was issued on 4 April 1910, but the warrant could not be executed because on that date he had reached Pondicherry, then a French colony. The warrant against Aurobindo was withdrawn.

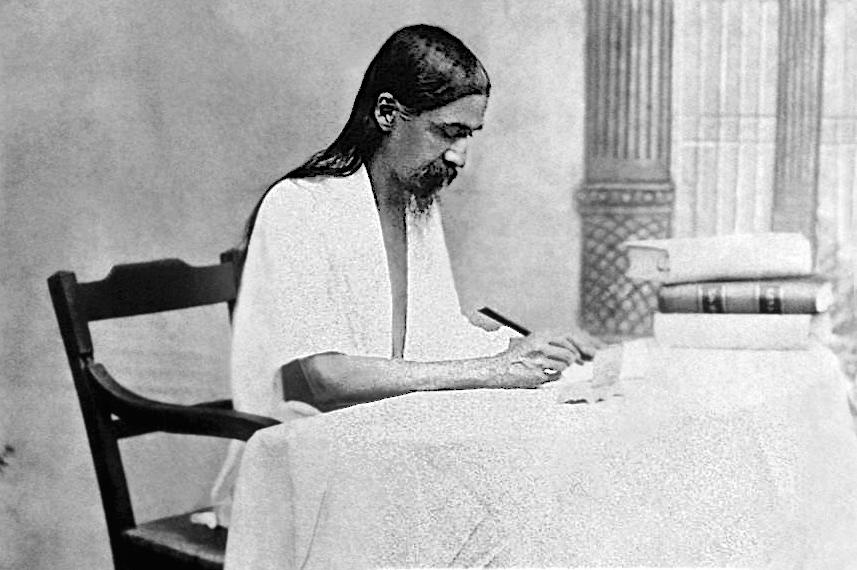

Aurobindo Ghose went to Pondicherry in 1910 and remained there till his death in 1950.In Pondicherry, Aurobindo dedicated himself to his spiritual and philosophical pursuits. In 1914, after four years of secluded yoga, he started a monthly philosophical magazine called Arya. This ceased publication in 1921.Some of the book series derived out of this publication was The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, Essays on The Gita, The Secret of The Veda, among several others.

Photograph of Aurobindo in Pondicherry

The Sri Aurobindo Ashram was set up in 1926. Around the same time he started to sign himself as Sri Aurobindo, Sri being commonly used as an honorific. Together with his spiritual collaborator, Mirra Alfassa, (The Mother), he led a community of disciples towards spiritual uplift and social work with special emphasis on education.

On 15 August 1947, Sri Aurobindo strongly opposed the partition of India, stating in an interview to Francois Gaultier, that he hoped "the Nation will not accept the settled fact as forever settled, or as anything more than a temporary expedient”.

Sri Aurobindo was nominated twice for the Nobel prize without it being awarded, in 1943 for the Nobel award in Literature and in 1950 for the Nobel award in Peace.

Sri Aurobindo died on 5 December 1950, of uremia. Around 60,000 people attended to see his body resting peacefully. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and the President Rajendra Prasad praised him for his contribution to Yogic philosophy and the independence movement. Aurobindo led an extraordinary life, and left behind a legacy that was both controversial and indelible. His nationalistic engagements, spiritual pursuits, journalistic exploits exhibit his exceptionally gifted mind and spirit. It is perhaps for this reason that American philosopher Ken Wilber has called Sri Aurobindo "India's greatest modern philosopher sage".

Sri Aurobindo before his last rites

Commemorative postal stamp on Sri Aurobindo in 1964